Mad World on Kritik: Mad Men Season 4.4

"The Coolest Medium"

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

posted under

Hansen

,

Mad Men

,

Mad World

,

McLuhan

,

Medium Cool

by Unit for Criticism

[Here is the fourth in our multi-authored series of posts on Mad Men season 4, posted before the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s (Duke University Press.]

"THE COOLEST MEDIUM"

Written by Jim Hansen (English)

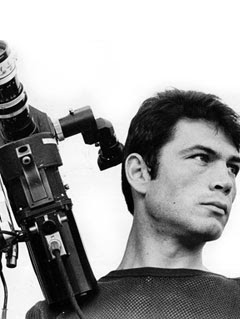

At the climax of Medium Cool, Haskell Wexler’s 1969 film, we find the former news cameraman John Cassellis (Robert Foster), caught in the clash between the young protestors at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the National Guard. Coming near the conclusion of a film that operates as a critique of the medium of television—a film that works as a patchwork of cinéma vérité, actual documentary footage, and romance-plot—this particular scene with Cassellis as witness (someone who has come neither to protest the current order nor to maintain that order) has always struck me as a peculiarly compelling one. He is there at the Chicago convention to watch one of those crossroads moments in American political and cultural history.

Although Cassellis starts off as a fairly jaded character, he ends up forging sympathetic attachments to several of the other characters in the film, most notably to the widow Eileen and her son. As Cassellis stands between the National Guard and the protestors in the midst of a film that, itself, stands between fiction and reality, we the viewers seem to be invited to make a choice. With whom will you side? Do you stand with the old guard, with those who represent the power structure and the current status quo, or do you stand with the youthful protestors, with those demanding change, with those who oppose the status quo?e

Although Cassellis starts off as a fairly jaded character, he ends up forging sympathetic attachments to several of the other characters in the film, most notably to the widow Eileen and her son. As Cassellis stands between the National Guard and the protestors in the midst of a film that, itself, stands between fiction and reality, we the viewers seem to be invited to make a choice. With whom will you side? Do you stand with the old guard, with those who represent the power structure and the current status quo, or do you stand with the youthful protestors, with those demanding change, with those who oppose the status quo?e

A similar moment marks the ending of Episode 4 of Mad Men, “The Rejected.” As Peggy Olson, whom we have seen rise from secretary to copywriter, leaves for lunch, she stands between the male executives of Sterling, Cooper, Draper, Pryce and Vicks Chemical Company all clad in classic blue or gray suits on one side and her new bohemian friends clad in warm, earth-tone street clothes on the other. Like Cassellis, Peggy faces a decision. Like the viewers of Medium Cool, so do we.

Mad Men has always been a show about the 1960s, of course, and perhaps I’ve always hoped that at some point we’d catch Don Draper listening to Sgt. Pepper, dropping acid, growing out his hair, and discovering some mind-blowing inner truth about himself. He is, after all, a character defined by the malleability of identity—that is, by his capacity to alter his persona. I often forget, however, that Mad Men is also a show about the changing of the guard, a show about an eager new generation, represented for the most part by younger characters like Peggy and Pete Campbell, who confront an old guard represented by the likes of Roger Sterling, Bert Cooper, and—yes—even Don Draper. For all of his dynamism and slick charm, for all of his capacity to read a social or cultural situation so brilliantly that he can reshape the desires and motives of those around him, Don remains part of an old guard, the master of a world that is very quickly dissolving.

Mad Men has always been a show about the 1960s, of course, and perhaps I’ve always hoped that at some point we’d catch Don Draper listening to Sgt. Pepper, dropping acid, growing out his hair, and discovering some mind-blowing inner truth about himself. He is, after all, a character defined by the malleability of identity—that is, by his capacity to alter his persona. I often forget, however, that Mad Men is also a show about the changing of the guard, a show about an eager new generation, represented for the most part by younger characters like Peggy and Pete Campbell, who confront an old guard represented by the likes of Roger Sterling, Bert Cooper, and—yes—even Don Draper. For all of his dynamism and slick charm, for all of his capacity to read a social or cultural situation so brilliantly that he can reshape the desires and motives of those around him, Don remains part of an old guard, the master of a world that is very quickly dissolving.

It will shock you how much this really happened

From the show’s inception we’ve seen Peggy and Pete watch Don with envy, dedication, hostility, and awe. They have, in some ways, desired him, desired to be him, and, in particular, desired to have his easy, suave charm. They openly compete for Don’s approval, and Peggy and Pete are even briefly lovers. Their responses to Don have helped to define the series. Will they choose to be like him? Could they emulate him even if they really wanted to? But Don’s life has been changing of late. In Season 1, we saw him walk nonchalantly between the varied worlds of Sterling Cooper, his suburban family, and his bohemian girlfriend, Midge. Now he often appears alone in his claustral Manhattan apartment.

In the Season 2 episode “The New Girl,” after Peggy secretly delivers her “illegitimate” child, Don visits her in the hospital. He looks down at her and advises her to forget the past and move on with her life. "It will shock you how much it never happened,” he tells her (in a line my colleague Rob Rushing chose for the title of his chapter in the Mad World volume). In such early scenes, Peggy was clearly the disempowered young girl, and Don was the sage manipulator of personas (and persons), the skillful executive who poured drinks for clients, charmed women, and counseled the young and talented.

In Season 4, however, he is divorced from Betty, mostly friendless, and beaten down. And I’d like to point out that it’s not nearly as much fun to watch a bruised and powerless Don Draper in Season 4 as it was to watch a canny Don out-drink and humiliate Roger in Season 1. In “The Rejected,” Don’s secretary, Allison, with whom he has had one rather degrading sexual encounter, openly refers to him as a “drunk.” In fact, when Allison finally manages to work up the courage to confront Don about their encounter she insists, “This actually happened!” A rather weary Don quietly replies, “I know.”

In the first and second seasons of Mad Men, Don seemed much more like a Wildean dandified survivor to me, much more like a character who could use wit, masquerade, and the capacity to read social situations to maneuver past nearly any obstacle, much more like someone who could say, with confidence, “this never happened.” By the third season, as he worked to hang on to his life with Betty and the children, he seemed less capable of controlling his identity or manipulating his various masks. No longer the master illusionist who can advise Peggy that she will be shocked by the ease with which we can all change, forget, overlook, or conceal our own history, Don looks more like a prisoner of his own contrivance now.

Thus, in “The Rejected,” after an infuriated Allison throws a paperweight at Don and storms out of his office, Peggy, standing on her desk in the next office, gazes down through the window as Don very morosely pours himself a drink. The situation we saw unfold in Season 2 has reversed itself as Don is quite literally beneath Peggy in this scene. She looks down on him, but she offers no advice.

Thus, in “The Rejected,” after an infuriated Allison throws a paperweight at Don and storms out of his office, Peggy, standing on her desk in the next office, gazes down through the window as Don very morosely pours himself a drink. The situation we saw unfold in Season 2 has reversed itself as Don is quite literally beneath Peggy in this scene. She looks down on him, but she offers no advice.

As Peggy stands between the corporate executives and the sixties bohemians at the end of the episode, the show provides us with a number of important and overlapping choices. Besides the obvious one between work and fun, Peggy must choose between the old guard and the new, between men in their sixties and the 1960s, between a life defined by the corporate ladder and one defined by the historical moment.

The same episode finds Pete winning the Vicks account by extorting a promise from his father-in-law, and Peggy proceeding with the Pond’s cold cream account. The firm’s younger generation is clearly in its ascendancy on the show. Pete has evidently chosen the more cutthroat world of the executive who does business with lead-pipe cruelty. Peggy chooses to go out with the bohemian crowd. Don, significantly, is not even there, though Pete claims that the executive crowd waits for him. For once, Don appears to be out of choices. When the world got too rough for Dick Whitman, he merely took on a new identity. What will Don Draper do when things get too rough for him?

The same episode finds Pete winning the Vicks account by extorting a promise from his father-in-law, and Peggy proceeding with the Pond’s cold cream account. The firm’s younger generation is clearly in its ascendancy on the show. Pete has evidently chosen the more cutthroat world of the executive who does business with lead-pipe cruelty. Peggy chooses to go out with the bohemian crowd. Don, significantly, is not even there, though Pete claims that the executive crowd waits for him. For once, Don appears to be out of choices. When the world got too rough for Dick Whitman, he merely took on a new identity. What will Don Draper do when things get too rough for him?

Medium Cool derives its name from Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 study, Understanding Media. For McLuhan, different forms of mass media allow for different levels of viewer participation. Subsequently, McLuhan defines the films that preceded the 1960s as “Hot Media” because such movies delivered visual narratives so fully that its viewers had to do very little thinking to fit the pieces of narrative together.

On the other hand, McLuhan defines television, with its quick cuts to commercials and its apparently open debates about opinion, as a “Cool Medium”: a medium that invites a great deal of thinking, a medium that requires much of its viewers. “The Rejected” refuses to tell us whether Peggy or Pete (who will soon become a father) has chosen the road to future happiness. By McLuhan’s definition Mad Men, whatever else it may be, remains among the coolest media around today.

"THE COOLEST MEDIUM"

Written by Jim Hansen (English)

At the climax of Medium Cool, Haskell Wexler’s 1969 film, we find the former news cameraman John Cassellis (Robert Foster), caught in the clash between the young protestors at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the National Guard. Coming near the conclusion of a film that operates as a critique of the medium of television—a film that works as a patchwork of cinéma vérité, actual documentary footage, and romance-plot—this particular scene with Cassellis as witness (someone who has come neither to protest the current order nor to maintain that order) has always struck me as a peculiarly compelling one. He is there at the Chicago convention to watch one of those crossroads moments in American political and cultural history.

Although Cassellis starts off as a fairly jaded character, he ends up forging sympathetic attachments to several of the other characters in the film, most notably to the widow Eileen and her son. As Cassellis stands between the National Guard and the protestors in the midst of a film that, itself, stands between fiction and reality, we the viewers seem to be invited to make a choice. With whom will you side? Do you stand with the old guard, with those who represent the power structure and the current status quo, or do you stand with the youthful protestors, with those demanding change, with those who oppose the status quo?e

Although Cassellis starts off as a fairly jaded character, he ends up forging sympathetic attachments to several of the other characters in the film, most notably to the widow Eileen and her son. As Cassellis stands between the National Guard and the protestors in the midst of a film that, itself, stands between fiction and reality, we the viewers seem to be invited to make a choice. With whom will you side? Do you stand with the old guard, with those who represent the power structure and the current status quo, or do you stand with the youthful protestors, with those demanding change, with those who oppose the status quo?eA similar moment marks the ending of Episode 4 of Mad Men, “The Rejected.” As Peggy Olson, whom we have seen rise from secretary to copywriter, leaves for lunch, she stands between the male executives of Sterling, Cooper, Draper, Pryce and Vicks Chemical Company all clad in classic blue or gray suits on one side and her new bohemian friends clad in warm, earth-tone street clothes on the other. Like Cassellis, Peggy faces a decision. Like the viewers of Medium Cool, so do we.

Mad Men has always been a show about the 1960s, of course, and perhaps I’ve always hoped that at some point we’d catch Don Draper listening to Sgt. Pepper, dropping acid, growing out his hair, and discovering some mind-blowing inner truth about himself. He is, after all, a character defined by the malleability of identity—that is, by his capacity to alter his persona. I often forget, however, that Mad Men is also a show about the changing of the guard, a show about an eager new generation, represented for the most part by younger characters like Peggy and Pete Campbell, who confront an old guard represented by the likes of Roger Sterling, Bert Cooper, and—yes—even Don Draper. For all of his dynamism and slick charm, for all of his capacity to read a social or cultural situation so brilliantly that he can reshape the desires and motives of those around him, Don remains part of an old guard, the master of a world that is very quickly dissolving.

Mad Men has always been a show about the 1960s, of course, and perhaps I’ve always hoped that at some point we’d catch Don Draper listening to Sgt. Pepper, dropping acid, growing out his hair, and discovering some mind-blowing inner truth about himself. He is, after all, a character defined by the malleability of identity—that is, by his capacity to alter his persona. I often forget, however, that Mad Men is also a show about the changing of the guard, a show about an eager new generation, represented for the most part by younger characters like Peggy and Pete Campbell, who confront an old guard represented by the likes of Roger Sterling, Bert Cooper, and—yes—even Don Draper. For all of his dynamism and slick charm, for all of his capacity to read a social or cultural situation so brilliantly that he can reshape the desires and motives of those around him, Don remains part of an old guard, the master of a world that is very quickly dissolving.It will shock you how much this really happened

From the show’s inception we’ve seen Peggy and Pete watch Don with envy, dedication, hostility, and awe. They have, in some ways, desired him, desired to be him, and, in particular, desired to have his easy, suave charm. They openly compete for Don’s approval, and Peggy and Pete are even briefly lovers. Their responses to Don have helped to define the series. Will they choose to be like him? Could they emulate him even if they really wanted to? But Don’s life has been changing of late. In Season 1, we saw him walk nonchalantly between the varied worlds of Sterling Cooper, his suburban family, and his bohemian girlfriend, Midge. Now he often appears alone in his claustral Manhattan apartment.

In the Season 2 episode “The New Girl,” after Peggy secretly delivers her “illegitimate” child, Don visits her in the hospital. He looks down at her and advises her to forget the past and move on with her life. "It will shock you how much it never happened,” he tells her (in a line my colleague Rob Rushing chose for the title of his chapter in the Mad World volume). In such early scenes, Peggy was clearly the disempowered young girl, and Don was the sage manipulator of personas (and persons), the skillful executive who poured drinks for clients, charmed women, and counseled the young and talented.

In Season 4, however, he is divorced from Betty, mostly friendless, and beaten down. And I’d like to point out that it’s not nearly as much fun to watch a bruised and powerless Don Draper in Season 4 as it was to watch a canny Don out-drink and humiliate Roger in Season 1. In “The Rejected,” Don’s secretary, Allison, with whom he has had one rather degrading sexual encounter, openly refers to him as a “drunk.” In fact, when Allison finally manages to work up the courage to confront Don about their encounter she insists, “This actually happened!” A rather weary Don quietly replies, “I know.”

In the first and second seasons of Mad Men, Don seemed much more like a Wildean dandified survivor to me, much more like a character who could use wit, masquerade, and the capacity to read social situations to maneuver past nearly any obstacle, much more like someone who could say, with confidence, “this never happened.” By the third season, as he worked to hang on to his life with Betty and the children, he seemed less capable of controlling his identity or manipulating his various masks. No longer the master illusionist who can advise Peggy that she will be shocked by the ease with which we can all change, forget, overlook, or conceal our own history, Don looks more like a prisoner of his own contrivance now.

Thus, in “The Rejected,” after an infuriated Allison throws a paperweight at Don and storms out of his office, Peggy, standing on her desk in the next office, gazes down through the window as Don very morosely pours himself a drink. The situation we saw unfold in Season 2 has reversed itself as Don is quite literally beneath Peggy in this scene. She looks down on him, but she offers no advice.

Thus, in “The Rejected,” after an infuriated Allison throws a paperweight at Don and storms out of his office, Peggy, standing on her desk in the next office, gazes down through the window as Don very morosely pours himself a drink. The situation we saw unfold in Season 2 has reversed itself as Don is quite literally beneath Peggy in this scene. She looks down on him, but she offers no advice.As Peggy stands between the corporate executives and the sixties bohemians at the end of the episode, the show provides us with a number of important and overlapping choices. Besides the obvious one between work and fun, Peggy must choose between the old guard and the new, between men in their sixties and the 1960s, between a life defined by the corporate ladder and one defined by the historical moment.

The same episode finds Pete winning the Vicks account by extorting a promise from his father-in-law, and Peggy proceeding with the Pond’s cold cream account. The firm’s younger generation is clearly in its ascendancy on the show. Pete has evidently chosen the more cutthroat world of the executive who does business with lead-pipe cruelty. Peggy chooses to go out with the bohemian crowd. Don, significantly, is not even there, though Pete claims that the executive crowd waits for him. For once, Don appears to be out of choices. When the world got too rough for Dick Whitman, he merely took on a new identity. What will Don Draper do when things get too rough for him?

The same episode finds Pete winning the Vicks account by extorting a promise from his father-in-law, and Peggy proceeding with the Pond’s cold cream account. The firm’s younger generation is clearly in its ascendancy on the show. Pete has evidently chosen the more cutthroat world of the executive who does business with lead-pipe cruelty. Peggy chooses to go out with the bohemian crowd. Don, significantly, is not even there, though Pete claims that the executive crowd waits for him. For once, Don appears to be out of choices. When the world got too rough for Dick Whitman, he merely took on a new identity. What will Don Draper do when things get too rough for him?Medium Cool derives its name from Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 study, Understanding Media. For McLuhan, different forms of mass media allow for different levels of viewer participation. Subsequently, McLuhan defines the films that preceded the 1960s as “Hot Media” because such movies delivered visual narratives so fully that its viewers had to do very little thinking to fit the pieces of narrative together.

On the other hand, McLuhan defines television, with its quick cuts to commercials and its apparently open debates about opinion, as a “Cool Medium”: a medium that invites a great deal of thinking, a medium that requires much of its viewers. “The Rejected” refuses to tell us whether Peggy or Pete (who will soon become a father) has chosen the road to future happiness. By McLuhan’s definition Mad Men, whatever else it may be, remains among the coolest media around today.

10 comments:

A couple of things particularly caught my attention here: (1) "This particular scene with Cassellis as witness (someone who has come neither to protest the current order nor to maintain that order) has always struck me as a peculiarly compelling one." I must say, this has always been the position, taken consciously and unconsciously, willingly or unwillingly, that I find myself in. I'm mostly struck that you would also find it equally compelling, given that ethical engagement is normally your prime motivating factor; you don't strike me as a detached observer, and like Matt Wiener, your preference for the bohemian crowd is restrained but clear (and I should be clear, that such a preference is all but compelled by the show; after great lines like "You own your vagina"—"Yeah, but my boyfriend's renting it", how can one not love the young Turks at the gates of SCDP?).

(2) "I’ve always hoped that at some point we’d catch Don Draper listening to Sgt. Pepper, dropping acid, growing out his hair, and discovering some mind-blowing inner truth about himself." Here I couldn't disagree more. I detest the contemporary trend toward the dissolution of consistent "character," the constant switching between Jack and Locke on LOST, the reinvention of every character as "the thing you least expect" (but that I had kind of always kind of suspected because, you know, we're just not that dumb). To me, Don with long hair, Don finding himself, Don mellowed and grokking the whole vibe—that's just a complete betrayal of who the character was to begin with. I can totally picture Don dissolving his identity—as he's so often threatened to do—and moving to California to take up with the nascent Europhile jet set who are starting up free love communes; but he'll still be the semi-tragic, power-hungry "Dick" who sleeps with all the women and ascends the symbolic ladder when he gets a chance.

Yes MM is a cool medium. Viewers have to complete the picture that is offered to them, which allow us to offer many different pictures.

So, yes, there is a choice to be made, as shown by this scene of Peggy with the hipsters and Pete with the executives. They are separated by the glass doors. There are other glass separations in the episode: the young women in the focus group vs. the advertisers; Peggy vs. Don when she is peeking on him.

However, I think that the choice is not going to be between the hipsters and the squares, as discrete groups, but it is going to be a divide at the heart of the characters. Peggy might be looking down on Don without offering advice, but when she was talking to Allison earlier, she chose to do so in Don's office, and she told her to get over the fling (what beaten down and guilt ridden Don could only hint at when he told her that they were both adults). Peggy was unwittingly speaking for Don at that moment. The advice was given, not to him, but for him, and to Allison.

Similarly, old-fashioned Don defended Peggy's hypothesis about the Pond's campaign (based not a desire to marry, but a desire to indulge oneself), against the results of the psychologist's "research", telling her that he did not want to stay stuck in 1925. And of course, Don had been getting high with bohemians long before Peggy.

More deeply, the divide between the bohemians and the executives, the historical moment and the corporate ladder, is far more blurred than you let on. We certainly know, from our vantage point, that the corporations (and the agencies that did their advertising) will be quite adept at co-opting the new slogans and even the new ideas to further their reach. At the same time that the youthquake was happening, the Vietnam war was raging, and Nixon will finally be elected - though not with the help of Sterling Cooper. And yes there will be Sgt Pepper loving, acid-dropping, long-haired executives, who will be selling commodities and commodifying people's lives.

I agree with Rob that a hippy Don would make no sense in the context of his character and his story, and neither would a hippy Peggy.

Moreover, I don't want Don to throw away his suit (of armor). He looks too good wearing it.

Okay, so a number of things. First off, just to clarify the meaning of my original post: I don't think Don would ever or could ever turn into a hippy. I agree that such a change would not be consistent with the character. My post was intended to underscore that he would never make such a change, but perhaps I wasn't emphatic enough. Here's the problem as I see it: Since MM is a show that is ostensibly "about the 60s," I'm always tempted (and I think many others are, as well) to read the show allegorically. But I know full well that a good drama about the 60s can not also "embody" the 60s. In fact, Mad Men is a character driven drama, and such dramas operate best when we understand and know how the characters will behave. Buffy The Vampire Slayer (my all-time favorite show) is overtly allegorical. In the Buffyverse it's obvious that High School is Hell, that your first serious boyfriend turns into a monster after you sleep with him, etc..., but the show also works as a drama precisely because the characters end up driving the narrative and--eventually--reshaping the show's allegorical format. I firmly believe that strong characters can change, but they never change in irrational ways (unlike real human beings or characters in an Ionesco play). As a show about something, Mad Men, like Buffy, operates on two planes that occasionally intersect: The allegorical and the characterological. At the allegorical level, it represents the choices, ambivalences, changes, and historical dilemmas of the 60s. At the characterological level, it provides us with people trying to negotiate their identities and paths through the world. When characters struggling through life run into big 60s era choices, changes, and dilemmas twe get interesting drama, but the characters can never merely be in service to the allegory. This is all to say that I don't think the show is "Draper's Progress." Don never acts as a swinging 60s version of Bunyan's Pilgrim. If you want that kind of thing, watch some Oliver Stone movies.

As far as the ethical problematic from _Medium Cool_ goes, the choice seems fairly clear to me, but I also get the fact that real art is the kind of thing that calls the way I think and feel about the world into question. The moment of "choice" in the film is profoundly chaotic and troubling. While I would likely side with the protestors, I also understand that the film works very hard to get me to question the way I see things. That makes it art, for me.

As Jim notes so well, this episode continues the thematic of youth/age and the behaviors and values that each side represents. As I noted last week, Don imagines that he doesn't have to choose, that he can be the fulcrum that links them productively. I doubted that he can actually do this. This episode shows Peggy beginning to try to occupy the same position, to have a foot in each camp like Don. My sense is that neither Peggy nor Don will find a happy home in either camp. Jim reads the end of MEDIUM COOL as a call to choose, though it could as easily reinforce our spectatorial passivity, that we would be content just to watch and witness. Of course, nothing changes if we watch, but we risk little personally. Since Don has lost nearly everything, perhaps risk won't put him off as it has done up to now.

I once had a younger colleague tell me that she was glad that she hadn't been alive during the 1960s. After getting over my shock, I asked her why. "Too many choices, too many alternatives," she said. I can see that view behind these recent episodes of MAD MEN: not the choices (martinis, marijuana; Madison Avenue, the East Village), but the uncomfortable sensation of having to choose, maybe for the first time.

This is such a great conversation: thanks to Jim and all the commentators so far for making it possible.

Jim: I totally agree that the form of MM (as of most good realist genres) asks to be looked at allegorically as well as in terms of prevailing character structures. MM is indeed character-driven: much more I think than other “quality” shows (viz. The Sopranos) which have great characters but rely heavily on contingencies and oscillating narrative forms (surreal weirdness and so forth). In comparison to Tony’s story Don’s narrative arc is almost wholly determined by his character flaws, almost as though he were King Lear or a character in a George Eliot novel. I think one of the interesting things about S4 is that it’s no longer relatively easy to predict what those flaw will yield (as it was when the unmasking of Don’s identity and the break-up of the Draper family were so manifestly bound to happen). All that said, I still think the allegory isn’t so much about the 60s as about what the 60s means to us—those early 60s that MM has brought into consciousness like some return of the culturally repressed.

I’m at a loss in that I’ve never seen Medium Cool (!) so I can’t weigh in on the question of the choice in presents to us; though I find what Jim, Rob, and Sandy have said about it to be so intriguing. This is going on the Netflix queue.

One thing that may complicate this discussion of Peggy’s choice just a bit is her having been situated in this episode as “The Rejected.” That is, she was visibly pained (this surprised me a little) that Pete and Trudy will have a child together after all. When she looks at him with the older guys through the glass (perhaps recognizing him as one whose lifestyle choices, including now fatherhood, have aligned him with the status quo despite the hints of hipness in his character) there is a sense of regret, almost as though she is joining the hipsters partly by chance rather than fate. So I think that what choices there are for these characters are (as Zina has said) internal to them. If Don has been like a tragic hero with his fate more or less evident (thus far), Peggy is the most open character: the most subject and prone to contingencies. She is an open enough character that we don’t know what will come next: an affair with another guy like Duck or someone like the guy in the closet? She tends to take what life offers more than anyone else does. Though what a metaphor that closet was, reminding me that for all her openness, she unlikely to date another woman. But, then, who knows?

OTOH she has identified herself with Don—wanting to become him, not to sleep with him. And I think that’s part of her reaction to Allison. She is both reflexively loyal to Don who is her mentor in so many ways (we saw this loyalty when she dealt with Lois back in S2) and I think a bit upset to discover that Allison has apparently had with Don the sexual relationship that he gave her to believe he didn’t want from his secretary. She is also in the process of discovering that this idealization of Don is not shared by the bohemian world: a world in which “writing” advertising copy is selling out. That said, vis-à-vis Faye Miller (as Zina also made clear) Peggy clearly stands for a new female perspective. If some part of her would have liked to marry Pete, or at least continue the relationship with him; and another part of imagines herself as a female version of Don; yet another part comes out in her idea that women can get pleasure out of self-care (the nighttime ritual involving the cold cream) which is a kind of auto-eroticism. (The idea might seem shallow rather than new were it not pitted so clearly against the women who only want to get married—as though they took their cues from Freddy’s dated assumption about young women’s ambitions.)

P.S. I’m totally intrigued by Faye: the first woman (or person) who didn’t ask “Who is Don Draper?” but instead assumed he was just a “type” and told him so. How great was that? MM has had such a hostile relation to marketing research as though it and the “creative” side of advertising were worlds apart. Remember the Freudian-inflected marketing research of Greta Guttman in the pilot? It’s hard to believe that the writers have any plans to Guttmanize Faye—even if that were possible. I’m looking forward to where this will go. It’s clear that MM is moving beyond the world in which Don could stand out as an artist-maverick in contrast to a Guttmanized representation of marketing; and beyond the ease with which he parried Midge’s bohemian friends back in S1. I really like the way this historical question is rendered through an advertising question: marriage or autoerotic self-care; marketing or "creative"?

I kind of hope the rock-and-roll masculinity issue (which came up last week) will be handled in the same way: so that we can see Don’s response to, say, the Rolling Stones through the lens of advertising and without having to watch him air guitar his way through “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.”

Sorry, I just noticed a bad typo. When I wrote: "When she looks at him with the older guys through the glass (perhaps recognizing him as one whose lifestyle choices, including now fatherhood, have aligned him with the status quo despite the hints of hipness in his character) there is a sense of regret, almost as though she is joining the hipsters partly by chance rather than fate," I meant to say "almost as though she joining the hipsters partly by chance rather than CHOICE."

Hi Lauren,

Great point on Faye being the first one to not be intrigued by Don, and seeing no mystery in him. Whether it is a sign of uncanny insight or of obtuseness is still not clear to me. As late as S4E1, Roger was still telling Don : Who knows anything about you?

About the opposition marketing/creative, I think it can be also interpreted at a meta-level, MW's jab at the usual focus-group driven TV shows and movies, with happy endings, likable characters, easily overcome setbacks, etc.

As far as auto-erotic self care, it brings me back to the Relaxicizor - one of the early great episodes of a Don-Peggy connection and complicity.

Zina: "Whether it is a sign of uncanny insight or of obtuseness is still not clear to me."

I expect we will find it some Hegelian synthesis of the two.

Relaxicizor, great.

Hey!

I've entered a contest to win a walk-on role on that retro-licious TV show, "Mad Men".

If you wouldn't mind taking two seconds to vote for me, I would really appreciate it.

Click on my name above to go to my blog and vote.

Thanks so much!

MadMenGirl

Post a Comment